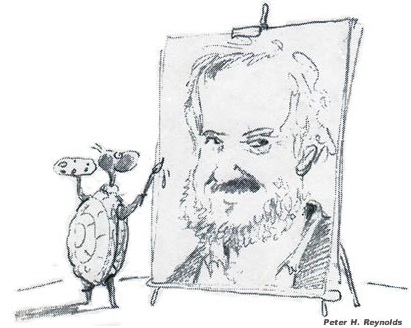

Alan Kay and Seymour Papert testify before a rogue’s gallery of Congressional misfits and a clueless venture capitalist.

In October 1995, the House Committee Economic and Educational Opportunities and House Science Committees held a nearly three-hour hearing to examine “technological advances in education.” The first two hours or so of the hearing are a real hoot (as all the crazy kids on Capitol Hill say).

The first panel consists of the father of educational computing, Dr. Seymour Papert; Alan Kay, the inventor of the term “personal computer” and many of its accompanying technologies; Harvard Professor Chris Dede; and a clueless venture capitalist, David Shaw, who gave a lot of money to the Clinton Campaign. It’s worth mentioning that David Shaw once employed Jeff Bezos and passed on investing in Amazon.com at its inception.

Papert starts his testimony like he was shot out of a cannon. Alan Kay says that he agrees with Seymour and then throws gasoline on the fire. The Wall Street stiff decides to argue with Dr. Papert while the Congress bangs the gavel in an attempt to restore order.

The discussion is well worth two hours of your time if you care about the edtech or the future of education.

I remember seeing the hearing when it first aired and have cherished a 3rd generation VHS recording. Now I can share it with you and my students via the Web! The Daily Papert has also transcribed the hearing so it may be preserved for future scholarship.

When I originally saw the hearing, back in 1995, I remember thinking that the members of the Congressional Education Committee may not be our nation’s best and brightest. Watch the hearing today and you can’t help notice that naughty underage male Congressional Page sexting aficionado, Mark Foley, plus convicted felons, Duke Cunningham and Chaka Fattah, interrogating some of the most thoughtful educational thinkers in the world.

Transcript

“Technology In Education Witnesses testified on technological advances in education.”

On October 15, 1995, there was an extraordinary Congressional hearing discussing educational technology and the future of education. Alan Kay and Seymour Papert battled a venture capitalist and a Congressional committee comprised of (future) felons, low-information voters, and men involved in sex scandals.

Video link: https://www.c-span.org/video/?67583-1/technology-education

Robert Walker: Good morning. I’d like to welcome everyone to a hearing on Educational Technology. I think it’s going to be a very exciting hearing. I was excited yesterday to have an opportunity to see the classroom of the future, and now to talk about some of the issues, I think, would make it for a very worthwhile day. I’m very pleased that Chairman Bill Goodling and the members of his committee, the Empowerment and Education Committee have really cooperated with us in putting this together. I’m pleased to welcome Chairman Goodling here today to be a part of this session; also Ranking Member Bill Clay, when he arrives. I’m sorry. There he is. All right. Bill, welcome.

Bill Clay: I’m here, Bob.

Robert Walker: Of course the Ranking Member of the Science Committee, George Brown. This is, as I say, I think an exciting glimpse into the future and I’m delighted that we have the kind of cooperation. What we’re going to try to do throughout the day is alternate in and out of the chair so that there is a shared jurisdiction over this hearing. We want to make certain that people understand that we’re examining not just technology issues. This is really about education, how education deals with the future.

Speaker Gingrich had hoped at some point that he was going to be able to come and testify. He’s not going to be able to do that with the press of other things. He is going to try to get over at some point today to the classroom of the future in 23-25. Any of you who have not had an opportunity to get there, we would certainly encourage you to go down and take a look at that display. It’s very fascinating.

What I’d like to do is begin by asking the committee chairmen and the ranking members who are here for their opening statements. For the first statement, I would turn to Chairman Goodling.

Bill Goodling: Is that on? The reason Mr. Clay was delayed over there coming in is, in our committee we usually have a drum roll when he comes in and he was waiting for that drum roll. I have an opening statement I’ll submit for the record, because I know we have a lot of people to testify, just to indicate that I’m very interested in the subject and very interested in hearing the testimony. Then hopefully at the end, you will all also give us some ideas of how you put the dysfunctional family back together again so that my wife doesn’t have to appear in a first grade class with 18 students, 12 of which are from dysfunctional families and try to figure out what it is she’s going to do to make sure they all receive an excellent education. I will submit my remarks for the record.

Robert Walker: Very good. I thank Mr. Goodling. Mr. Brown, opening statement?

George Brown: Mr. Chairman, recognizing the scope of what we’re doing and not designed to take up too much time, money was on my mind, I’ll tell you, let me welcome the distinguished witnesses that we have before us this morning. Let me indicate without amplifying on it that the chairman knows this Committee on Science has had a long involvement with the questions of educational technologies and a strong record of support for them.

Let me also ask unanimous consent to insert in the record a letter from the president science adviser indicating their strong support for the programs for enhancing education, which modern technology makes available to us. With that, I’ll ask unanimous consent to revise and extend my remarks.

Robert Walker: I thank Mr. Brown. Mr. Clay?

Bill Clay: Thank you, Mr. Chairman. I also want to welcome the distinguished panelists today and I look forward to your testimony. I would like to also submit my statement for the record.

Robert Walker: Thank you, Mr. Clay.

Bill Goodling: Mr. Clay didn’t introduce our new member. Would you like to introduce our new member?

Bill Clay: Is he here?

Bill Goodling: Yes. He’s down on the end.

Bill Clay: Mr. Fattah is the new member of the economic and … What is it? Education and Economic Opportunity Committee, EEOC, for the Republicans. That’s oxymoron. I’d like to introduce our new committee member. This is his first meeting, Mr. Chaka Fattah from Pennsylvania. Welcome to the committee.

Bill Goodling: Sometimes he doesn’t put oxy in front of that when he addresses us.

Robert Walker: There’s two fellow Pennsylvanians. Chairman Goodling and I are happy to welcome to the hearing today, and I’m sure that his committee …

Chaka Fattah: Did great school in Philly.

Robert Walker: I too will ask unanimous consent to submit an opening statement for the record. I’m looking forward here today to a very lively session that will give us a greater understanding of the massive changes likely to take place in the K through 12 curriculum over the next 20 years. That awareness will help us with future education legislation and may determine very much the destiny of the country.

With that, we would be pleased to welcome our first paneled witnesses. Other members with opening statement, I would say, we would ask you to submit them to the record so that we do have an opportunity to hear as many of our witnesses as possible. Without objection, we will take all opening statements that members may have prepared for the record. Do you have a question?

Chaka Fattah: I thank the chairman and the ranking member for their gracious …

Robert Walker: The microphone.

Chaka Fattah: I just wanted to thank the chairman and the ranking member for their gracious welcome to the committee. The chairman, I know from my work with the PHEAA agency back in Pennsylvania. The ranking member, Mr. Clay, I’m looking forward to working on the committee. Thank you.

Robert Walker: Good. We welcome you here today. With that, we’d like to invite first the witness, the panel of witnesses to the table. We thank you very much for being with us today. I have an order on my panel that seems to move across the table from my right to my left. I think what we’ll do is begin with Professor Papert. We would welcome your testimony.

Seymour Papert: Thank you. I see in front of me where there is no vision …

Robert Walker: Would you turn on the mic? I think that the mic …

Seymour Papert: It needs to be on. I see in front of me where there is no vision, the people perish. There is no vision in the education establishment about where education is going. I think that’s the main burden I’d like to make. I’d like to illustrate it by a series of parables rather than quote facts which in the short time. The first parable is about people in the 19th century who were doing research on how to improve transportation.

Somebody stumbled on the idea of a jet engine and had the great idea that if we attach the jet engine to the stage coach, it would assist the horses by adding to their power. In fact, the opposition to this idea said, “No, don’t do that. Let’s train the stage coaches better. Let’s study why the wheels squeak. Let’s make better grease.” They won because they did experiments and they got results, and the other guy, the jet engine caused the stage coach to disintegrate.

What we’re doing with technology in education is exactly analogous. We’re putting computers and other technology in a school system that was designed for a totally different epoch, where everything about it, the curriculum, its content, the idea of segregating children by ages, all this is the consequence of a system of knowledge technology called the blackboard or the slate or the pencil and paper that required the dissemination of knowledge through presentation bit by bit by teachers, so it had to be divided into subjects and the children had to be organized into grades. What could be taught was severely restricted by the conditions under which knowledge was disseminated.

I think that the problem is not how to stick the educational jet engine onto the educational stage coach. The problem is to invent the educational jet engine which is something that will be radically different in all its structure from what we see in schools today. I object strongly to what you saw being called a classroom of the future. It’s a classroom of the very, very, very near future. I doubt if there’ll be classrooms in the real future. There’ll be something else. Obviously, there’ll be places where children learn, but they won’t resemble what we see today.

I’d like to use one other little parable and that’s about, we have a strong opinion in this world that some people can do things like mathematics and some people can’t, and some people can learn languages and some people can’t. Just focus on mathematics. Why do we think some people don’t have a head for mathematics? It’s because they didn’t learn mathematics in the mathematics classroom. When we go into the French classroom and see how few children learn French, we do not conclude that they do not have a head for French, because we know that those very same children, if they grew up in France would speak French perfectly.

This is a total non sequitur that runs right through the whole thinking about our education, people’s abilities, and who can learn what at what age. The problem for mathematics education is not to find a better of teaching mathematics in the classroom. The problem is to find the analog of learning French by growing up in France. It’s to create a math land, math land being to mathematics what France is to French.

This is the great contribution of the computer. It’s not an automated teacher. It’s not a way of presenting the same old curriculum. It’s a mathematic-speaking being, a medium, an instrument that would give children and everybody the opportunity to learn subjects like mathematics that we have thought of as too hard, too formal, too abstract, to learn this in the same kind of natural way as children can learn to walk, to talk, to manipulate their parents, to do all the things their children learn to do, without an curriculum and without any of our quizzes or national standards. They just learn these things because they live in a learning environment.

Our job is to convert this new technology into the infrastructure for that environment. In order to do that, we have to understand that there’s an entire education establishment there. By that, I mean the administrations of the schools and the professors in the schools of education and the government agencies, this whole structure which has been built around supporting and understanding an outmoded system. I think one has got to understand that this education establishment has very divested interest, not only for their jobs, but more important in their vision.

Their vision is how to improve and keep going, the old system. Their vision is not how to envision and invent and foster the growth of something radically different. I think that that is the vision that we have to have. It’s very hard to know how to translate that vision into what to do on Monday in the classroom, and we have to face that dilemma, but I think we can. I think that the job, the leadership role that our government can give is to recognize that problem, to recognize that when we look into the not very distant future, 10 or 20 years, the present system will be totally antiquated in everybody’s eyes and I think we got to foster the growth of something new in order to make an orderly transition possible.

One last parable, which isn’t really a parable. I’m very struck by the analogy between the current state of our school system and the situation of the Soviet Union maybe 10 years ago when at the time that Gorbachev came into power. It become apparent that this system is collapsing, that it can’t operate, but it was also, although this is apparent from the outside to the people inside, they tried to fix by jiggering the details, by making local fixes within its bureaucracy.

I think we’re in exactly the same position in our choice of and our approach to trying to fix our education system, which needs a far more radical examination of what it’s about, what the problems are, why it is what it is. If we do that, I think we might find that one of the reasons is exactly the same as what was wrong in the Soviet Union where they had a command economy, where a committee somewhere decided on how many nails would be produced everywhere in the country.

This cannot work in the modern world. We in our education system are trying to run the closest thing to a command economy in the form of a command curriculum where somehow we think we can dictate. Whether it’s at a federal or state or local level, it doesn’t matter. We think we can dictate a same curriculum for every child irrespective of who that child is. I think this is impossible for exactly the same reason is going to collapse. We have to recognize this and the collapse and see.

Unless we make a faster, very rapid change in the system, it will break down in the same disorderly way that we are beginning to see in some cities now and we saw in the collapse of the Soviet command economy. I think that’s enough. Thank you.

Robert Walker: Thank you very much, Professor Papert. Dr. Kay?

Alan Kay: Thank you. I’d like to submit two documents for the record. One is a Scientific American article I wrote a few years ago, which I think covers a lot of the issues. Another one is a short piece I wrote for this hearing. In my few minutes …

Robert Walker: Without objection, it will be included in the record.

Alan Kay: Thank you. For my short time here, I’d first like to say that I got started working with children in technology because of a visit to Seymour Papert in 1968, 27 years ago or so now. I was struck immediately by his understanding and vision of how education and this new computer technology is going to play itself out. I think he was right then and I think he is right now.

There’s some real problems in making it work. If the issue were music, for instance, if America’s parents were worried that their children wouldn’t make it in life unless they became musicians by the time they left high school, we could imagine Congress or some state legislature coming up with the solution of “Let’s put a piano in every classroom.” They would say, “Unfortunately, we don’t have enough money to train the existing teachers or hire musicians. What we’ll do is we’ll just give the existing teachers two-week refresher courses in the summer on music, and that should solve our problem.”

We know that music as we know it is not really going to get into the classroom. Now, the children will really enjoy having a piano in the classroom. They’ll evolve a kind of chopsticks culture. It may be a little bit beyond, but that’s basically what we’re getting right now. Part of what math land is and part of what any kind of environment for doing rich learning in is one in which the adults are invested in it as well.

I think this is the biggest problem that we have to deal with, because obviously American technology can reduce as many computers for as low a cost as we need. We can saturate the entire world with computers, but to set up a sense of what its special music is, is going to be very, very difficult. I think that is what we should be aiming our efforts at.

I’d like to say one other thing, which is a rabbi famous for his wisdom in Europe was once asked why the Jews keep the Sabbath holy. He said, “Because man is not beast of burden.” What he meant by that was not just that you shouldn’t work one day a week, but he meant that, being human isn’t primarily about working. The most important thing here is to try and differentiate between all of the vocational demands that are being placed more and more heavily on society year by year, by parents, by businesses, and what education actually means.

If we take the pragmatic step of simply trying to deal with vocational problems and simply try and institute training via computers in our schools, we will lose the larger battle and we’ll lose it fairly soon. It’s in part because it is not nearly as difficult for people to learn how to do new jobs as it is for them to have the flexibility to have change be a part of their lives. One of the biggest problems in today’s business is not in the intelligence or ability of people to learn. It’s in the sense of having a large enough world view to see that there’s more things in life than the job that they’re doing right now. I think that’s a very important part.

The third thing I would like to mention is that, even though television is so deeply embedded in our society, it now seems to be the environment that people are exposed to. I think it is one of the worst things in the quantity that it is viewed for helping children understand how large the world is. People like to say that people find out more from television now than they ever did in the past. The problem is, what they find out is trivial, simple, and has very little to do with the kinds of thinking they’re going to have to do when they grow up.

Learning is very entertaining when you do it, but entertainment often isn’t particularly good learning. Maybe television should be the last technology that America product that doesn’t have a surgeon general’s warning on it. It’s something to think about.

Now, my recommendations are kind of flimsy, and the reason is because, as Seymour points out, we have an enormous situated bureaucracy for running education in this country. The biggest tragedy within it are many teachers who are completely dedicated to helping their student’s lives, but within this larger machine, I see very little chance of change in the direction that America needs. I think that is something that Congress and all of the people of this country are going to have to wrestle with for the next quite a few years.

I think setting up goals such as the America will be the first in the world in science and math, as President Bush did a few years ago, completely misses all of the points. One of the points it misses is that this is simply not possible, take decades to make changes from what has happened. It also misses the point about what the goal should actually be. The goal should be much more like this famous rabbi which is that, “Schools should not be just for learning how to make a living, but learning how to live.” Thank you.

Robert Walker: Thank you, Dr. Kay. Professor Dede?

Chris Dede: I bring you good news and bad news about the future. The good news is that powerful learning technologies from high-performance computing and communications will enable K to 12 schools to move to a new model of education, distributed learning. Distributed learning is centered on collaborative learning through doing, orchestrated across classrooms and homes and workplaces and community settings. America’s information infrastructures are the crucial development that makes distributed learning possible, affordable and sustainable.

Knowledge Webs, virtual communities, shared synthetic environments, and sensory immersion are four new technological capabilities shaping distributed learning. Knowledge Webs give students access to experts, archives, and shared investigations. As with the World Wide Web on the Internet, links between chunks of information will help teachers and learners to interrelate and contextualize ideas. Virtual communities based on telepresence, the communication of emotion across barriers of distance and time, will encourage and motivate learners. For example, tele-mentoring and tele-apprenticeships will provide both the intellectual and the interpersonal support, important in bridging from school to work.

Shared synthetic environments will extend students’ experiences by enabling learners and educators at different locations to inhabit and shape a common virtual world. This offers the possibility of learning through doing and virtual offices, factories, hospitals, and even imaginary environments similar to those on Star Trek’s holodeck. Video game consoles capable of implementing these virtual experiences will be everywhere, even in poor and rural households. Advances in artificial reality will place students inside virtual worlds with intriguing things to see, hear, and touch. Such sensory immersion is powerful and deepening learner’s motivation and their intuitions about physical phenomenon.

My current research centers on assessing the potential value of virtual worlds, designed to teach material as disparate as electromagnetic fields and intercultural sensitivities. Using these and other new capabilities for distributed learning is crucial to enhancing the creativity, sophisticated thinking skills, ability to apply ideas, and motivation of K to 12 students. This is vital for America’s future economic well-being and for meeting the challenges of citizenship in a knowledge-based society.

Given all these advances, what’s the bad news? The bad news is that technological advances alone are insufficient to leverage educational change. In 1975, in the early days of micro-computers, accurate forecast of the extent and power of today’s technology would have seemed preposterous. Few would have believed that two decades later, desktop machines much more powerful than 1975’s supercomputers would be routinely available in workplaces, schools, and many homes that by 1995, these powerful available technologies would not have completely transformed schooling and learning, would have seemed even more incredible.

Yet, widespread major gains and learning outcomes or motivation have not occurred, even though isolated examples of innovation through educational technology have demonstrated very significant effects. If all computers and telecommunications were to disappear tomorrow, education would be the least affected of society’s institutions.

Those who do not understand history are doomed to repeat it. Three reasons that educational technology has made a limited impact to date are: First, the major focus of educational technology implementation has been automating marginally effective models of presentational teaching rather than innovating via new models of learning through doing. Second, has been seen as something that happens through teaching students in isolated schooling settings, rather than through empowering and interrelating learning in classrooms, homes, communities, workplaces, and via the media.

I would disagree somewhat with the prior two speakers. These two assumptions are not simply part of the education bureaucracy. These are deeply rooted in our culture and the educational institutions that have made attempts to go beyond these two assumptions have often been [requested 00:28:24] by the communities that they serve because parents and taxpayers and citizens also believe these two limiting things about education. Third, teachers and school administrators are overwhelmed by their current responsibilities and they do not currently have the support systems necessary to re-conceptualize their educational roles.

In brief, transforming education requires both building a top-down computing and communications infrastructure for our society and developing a second bottom-up human infrastructure of wise designers and educators and parents and citizens. My written testimony outlines changes in federal policy and federally sponsored research that would help to make this possible. Thank you for giving me the opportunity to share my ideas.

Robert Walker: Thank you very much. Dr. Shaw?

David Shaw: Thank you. Let’s see. Do I have to do something here? There we go. I’m deeply honored to be here and also very excited. Honored, because of my chance to address this body, but also very excited because I sense a confluence of interest in this area, which has been important to us for a long time now both from the legislative branch now and the executive branch, and also within the educational community and the educational research community, the educational technology research community. This makes me think that something is actually likely to happen, which is going to be very important for us over the years.

I’m delighted to see Congress’ interest, but I want to make sure everyone knows that the White House is also very seriously interested. I’ve had the honor of serving as president of the panel on Educational Technology of the President’s Committee of Advisors on Science and Technology, which has first of all brought me in contact with some of the people in the White House and in the Department of Education who are doing some remarkable work in this area, but also, and in some ways more important, brought me in contact with a number of the people out there who have been doing research and practicing in this area for a long time.

All of us I think have the sense that with bipartisan support, something important could happen now. What that importance actually is, I think, and I’ll be echoing what all three of the speakers had said so far, has probably 20% to do with technologies and 80% to do with what we do with those technologies. Because we haven’t said much about that and I sense that there may be some interest in it, let me just sketch the quick futurist sketch of what may happen, but I’m going to do it very quickly, partly because of time limitations and partly because I think you’ve heard this so many times that the words will start to sound like obviousities.

The first one is, computing speed and power and memory capacity is going to go up dramatically over the next 20 years. We don’t know exactly how fast because there could be unforeseen obstacles and unforeseen discoveries, but if I had to guess, I would guess that we’ll have about a hundred times the computing speed and memory capacity for an equivalent price by the year 2015. On the low end, we can expect to see the computing and memory resources that you’d find in the most powerful personal computer or workstation selling for well under $100, where the dominant cost is likely to be the actual I/O devices, the display devices and the data entry devices.

What that means is that, when those costs dominate, we’ll have to look to new technologies, for example, set-top TV boxes or handheld devices where we can get the cost down low enough that we can exploit the very low cost computing power. We’re also going to see dramatically increased communications bandwidth. The most obvious part of that is the Internet, which has caught the public’s attention in the last year.

My hope there is that we’ll Internet access become ubiquitous or nearly ubiquitous, and I’m particularly concerned with whether that’s going to reach people in rural communities and the inner cities, and some of the areas that if we’re not carefully looking at are likely to fall victim to being part of a bimodal distribution of information haves and have-nots in where we could actually exacerbate some of the problems that are besetting our communities right now rather than help them.

Assuming we do have that, electronic email is going to become nearly ubiquitous, at least for anyone with access to a computer. We’ll expect to see that be at least as common as fax machines and fax numbers, and possibly even approaching telephones. Other sorts of communications should be made possible by the fact that we’ll now be able to transmit not just short textual messages, but full-motion video, high-quality audio. In short, we’ll be able to communicate in all the ways that we’re used to doing, but over large geographical distances.

Now, what does this actually mean to us? Actually, I think what it means, it really comes from enabling technology and not from being central. If we focus too much on the raw technologies, even on such important things as connecting people to the Internet or getting a computer in every home, we may wind up in a situation where we have technology that’s not being used at all, much less being effectively used.

There are some things that are very important about computer-based technologies in education. One of the simplest ones and one of the ones we learned about even in very early drill and practice-based systems was that, you can individualize instruction. Students could learn on a self-pace basis so that, rather than having the teacher focus on some hypothetical typical student and then leave behind some of the students in the class and then have other ones be profoundly bored and have their attention wander, the student could basically find his own pace or her own pace and learn things that wouldn’t otherwise be learned.

Different modes of learning, visual learning, verbal learning, and textual learning, which are idiosyncratic to individual students are also supported by these technologies. I think the most important kinds of changes that can be supported by these new technologies really have to do with entirely new modes of learning.

If I had to summarize those just based on what I’ve learned in the past few months on the panel, I would say the most important things are that the student would assume a central role of the active architect of his or her own knowledge and skills rather than passively absorbing information that’s proffered by a teacher who’s sitting in front of the classroom. Second thing would be that, basic skills wouldn’t be learned in isolation, but in the course of undertaking various higher world tasks and integrating a number of basic skills in the course of solving these real world problems.

Information resources would also be key, but the large importance of that really comes from having the student be able to access those when they’re really needed to solve real problems rather than have a forced centralized curriculum. I’d also expect to see fewer topics covered than is the case with the traditional paradigm in education, but have those topics explored in more depth and in a very student-directed way.

Finally, greater attention is likely to be given to the acquisition of higher-order thinking and problem-solving skills with less of an emphasis on the assimilation of large body of isolated facts. That really represents a transformation in education itself. The use of technology, that is profoundly important, but the use of the human beings who are participating in this process are also going to be transformed in part because of technology, but in part, they’ll transform the way technology is used.

Teachers will still be important and for those of us who are expecting that we’ll have an increase in productivity because aggregate teacher compensation will drop because computers will take over their jobs, that’s not likely to actually happen. I think what’s much more likely is the teacher will become a coach, a monitor walking around the classroom, seeing what the individual students are doing, helping out in a very different roles than before.

The other thing that I think is going to be important is involving parents in the community. Technology, particularly to the extent that we have access in the homes, will be a key part in that also. If parents can communicate better with teachers, if teachers can communicate better with each other, if the community can be tied together, we’re going to see repercussions not just for the community, but for the quality of education.

As far as how we get there, I think this group and Congress, in the large, is going to have a major influence on whether it happens and how it happens. Unfortunately, some part of that has to do with spending. We’re now spending about 1.3% of the education budget on technology. Best estimates are, it will take 3 to 5% depending on exactly what we do. What’s more, the federal government now spends a disproportionate share of its education budget on technology. If that becomes cut down, what we’re going to see is much less technology in the schools.

Even more important is research and evaluation. It’s particularly important because, first of all, we don’t know what kinds of educational technologies work, and, secondly, there’s an economic externality. There’s a good theoretical reason to believe that if this sort of research is not funded at the federal level, it won’t be done. The reason is that, if a private company does it, it won’t be able to appropriate the full returns from its investment. If you develop a software product for education and it works, the competitors copy it, and your investment winds up dissipated among all of your competitors.

We could do it at the state and local levels, but we’d have a similar free rider problem. In short, there’s much that we have to do, much of it has to be done at the federal level and I hope we do that.

Robert Walker: Thank you very much. I appreciate all of your testimony. What we want to do is go to questions of members. We’re going to enforce a five-minute rule. We have lots of members here and lots of people on panels. I’m going to try to have us live within a five-minute rule of questioning. Let me begin with just a couple of questions here.

Profess Papert, you said something to the effect that in the future that there’s going to be a place where children learn, but it won’t like today’s classroom. Would you give us an idea what you think it will look like?

Seymour Papert: Maybe it will look like a research lab. Maybe it will look like an active, creative architect office. I think it will look like a place where people are engaged, young people of mixed ages. It was absurd that we should deprive eight-year-olds of contact with anyone except people at their own level of incompetence. People with mixed ages will be engaged in projects that are rich in knowledge and using the technology to research, get knowledge that they need in order to conduct long-term projects, maybe …

Robert Walker: Doesn’t that begin to look a little like the old one-room school?

Seymour Papert: I think the one-room school is a better model than the big massive high school building, yes.

Robert Walker: That’s interesting. Would you agree with the point that Dr. Shaw made that the teacher in that kind of setting becomes a coach, an information manager type of individual, rather than somebody who is imparting information as their prime function.

Seymour Papert: I agree with those words, but I’m afraid Mr. Shaw doesn’t get it. I think he’s phrased that the teacher, I quote, “will be a coach walking around the classroom seeing what the students are doing,” is a typical translation of a new concept into the old framework. There won’t be a classroom. The teacher won’t be walking around seeing what the kids are doing. The teacher might be part of this constructive project.

David Shaw: To be fair, most researchers now to whom I have spoken do not agree with Professor Papert on this point.

Seymour Papert: I did preface my remarks. I think there’s an education establishment that has its head wedged in a culture that grew up over a century during which there was the most lethargic progress in education of all fields of human activity, and they continue to suffer from being part of that culture. I think Congress ought to find some ways of planting seeds where there can be real radical change, real radical experiments which are not subject to the consensus of the researchers and other members of the education establishment.

Robert Walker: I promised you …

Seymour Papert: In my written testimony, I suggest that you could use the job call, for example, which belongs to the federal government as a place where real innovation could be made without many of the difficulties that tend, trying to introduce it into the classrooms. It wouldn’t even cost anything. All you’d have to do is to free the bidders for job call centers from the micromanagement of a sclerotic bureaucracy and let people who want to innovate innovate.

Robert Walker: I promised you a lively discussion. Let me go to the point that Dr. Shaw raised in terms of the specific terminology, but I think I heard it throughout all of your testimony and I just want to make certain I did. Do I hear each of you saying in some form that what technology promises to be able to give us the ability to individualize instructional programs and that it will be based then on the student’s talents, the student’s ability, the student’s intelligence, what the student brings? I assume this would be in consultation with parents and so on, as that instructional program would be designed.

Seymour Papert: No. No. We’ve got to give up the idea that learning is instruction. Instruction is a small part of learning. The important part of learning is doing. I think the big change is that we will move from an emphasis in instructionist thinking to constructionist thinking.

Robert Walker: Is it an individualized curriculum?

Seymour Papert: I think there will be individualized activities which will be of such a nature that each individual will be able to draw on personal strengths …

Robert Walker: Each student will not be learning the same thing as every others do?

Seymour Papert: Absolutely. That’s correct.

Robert Walker: It does.

Seymour Papert: [crosstalk 00:43:16]

Robert Walker: That’s individualized. Dr. Kay, would you agree that that’s …

Alan Kay: Yeah. If you look at six-year-olds, they are the greatest mathematicians they’ll probably ever be in their life. They’re the greatest scientists they’ll probably ever be in their life. They’re really great, in general. If math and science and so forth were easy, we could just let them invent it, but we know that it took thousands and thousands of years to actually make real progress.

The balance, I think, is that the students are inventive and creative and when an adult is involved, what an adult can do is they have some sense of where things might be going. The adults have some sense that the math might wind up in calculus some years down the road. That could have something to do with the kinds of things that the kids are encouraged to look at, but the kids have to invent it for themselves and the computer there can be a tremendous factor.

Nobody has been able to show yet a computer curriculum of any kind all by itself that when coupled with children will have the same effects as children in an atmosphere where adults really understand them and understand how to set up an environment in which all of their energies can be directed at learning, where the outcomes are likely to be fruitful.

Robert Walker: I’m going to try to stick by my own rules. The buzzer has sounded for my time, so I’m going to go to Mr. Goodling.

Bill Goodling: One comment and one question. Like Chairman Walker indicated that an awful lot did sound like the one-room school that I attended where Ms. Yost planted the seed and she wandered around the room just to see what we were doing to cultivate it. There were all ages together. A teacher today, of course, a good teacher could have them all the same age in the classroom, but the good teacher will have them at six, eight different levels. Whether they’re at a reading level in first grade or fifth grade and they’re still in first grade, it is still the same idea, but not a difference in age. It does sound like the one-room school.

My question is, everything I’ve seen in education would come along with new ideas and innovative technologies and so on, we generally institute them, and then we talk about training and preparing the teachers for the job. I haven’t seen anything changed. Perhaps, Professor Papert and Professor Dede could respond, maybe all of you could respond. Is anything changing in teacher education?

I haven’t seen anything and I’m just wondering if we make all the changes, is there anything going to happen as far as preparing the teacher or the observer or whatever we’re going to call the person in the future to handle the situation beyond all the other responsibilities they’ve had put upon them?

Chris Dede: There are slow changes taking place in teacher education, not as rapid as they need to be. Some of the answer for that is that the faculty of schools of education need to catch up to the 20th century. Some of the answer for that is that, our mechanisms of accreditation and what parents and communities expect of teachers often force teachers back into older models of teaching. In a sense, we say yes, we want a teacher that’s innovative, but I also want a teacher that was like the one that I learned so much from, that helped to be successful in life.

I think that until we evolve in the minds of parents and taxpayers and community members, a broader sense of what it means to do teaching and learning and a shared responsibility for that so that it’s not a matter of dry cleaning, where you drop off your student on the step in the morning and they come back brainwashed in the afternoon, when we get to a different and a more powerful model of that, then I think we’ll see the pressures for changes in teacher education increase.

Alan Kay: One of the things I mentioned was the piano as a metaphor, but we could also say 150 years ago, the response was, let’s put books in every classroom, and they are in every classroom, but in fact teaching is done from textbooks and is in accord with textbooks. Books are all about diversity of opinion and about learning at your own rate and about learning as deeply as you want. They’re all about individualized learning. Textbooks are about lockstep learning.

This is a perfect example of a great educational technology starting some 4 and 500 years ago that has actually been co-opted into much more of a party line from what it could be. I believe that’s exactly what is going to happen to computers. It’s what’s happening to computers in classrooms right now.

Seymour Papert: I think as far as the schools of education go, they’re sclerotic as the rest of the system and I’m not doing anything significant. However, I think there are wonderful people in the profession of teachers and I’ve seen some incredibly good learning conducted by individual teachers on their own time with their own effort, and that’s where I see the seed of real change. Some of the most interesting actions are the creation by teachers who are allowed in some school districts to start alternative schools where they can really pursue their own group of like-minded teachers, can pursue a different philosophy of education and really carry it out.

I think some of the wonderful things are happening in those areas. One thing that could be done at a national level would be to foster that sort of allowing the teacher who puts the energy and to learn something new to be able to carry that into practice. Too often, sadly, I’ve had teachers really work incredibly hard for a whole summer in a workshop that we’ve run and then go back to find that their excitement thing that carry this out in their classrooms is frustrated by the system into which they have to go back.

That’s one of the most heartbreaking things I’ve seen. I think if you can find a way to get around that by empowering those teachers, you will really plant some real seeds.

Bill Goodling: I was going to suggest that, unfortunately, oftentimes, the creative or innovative teacher is restricted. In just one quick example, supervising student teachers in Pittsburgh when the so-called missile crisis in Cuba, the headlines in the Pittsburgh paper said, “Missiles could hit Pittsburgh,” and I couldn’t wait to get there to see all of my student teachers talking about this possibility for the first time turning these kids on. Not one mentioned the headlines during the entire day. That night when I took them to test, they said, “We were told that we must stick strictly to the curriculum. We can’t deviate.” Thank you.

Robert Walker: Mr. Brown?

George Brown: Gentlemen, in the 1960s, there was a great upsurge of interest in radical ways of education, and much of it I’m sure you’re familiar with; classrooms without walls, getting involved in the community, that sort of thing. I had the pleasure being associated with a radical teacher by the name of Ivan Illich, who 25 years ago invited me to participate in a school he was conducting in Mexico where he had originally started out training Catholic priests for the service in Latin America, and he decided and part of the decision cost him his priesthood, that they had too many priests in Latin America and they didn’t need to send more down there.

He changed his school into one that taught not only language, but how to reform society. This strikes me as being somewhat close to the message that may be coming from you, that it’s not the technology so much, but how we can change the society and involve the students as a part of that society. I just ask you to comment on that and see if I’m anywhere close to being right.

Seymour Papert: Yes. I think it’s both sides of that. The techno-centric people who think that technology will solve it are totally wrong, but a little a parable for the other side. Leonardo da Vinci invented the helicopter, but there was no way in which you could actually make one because you would have needed a whole lot of other infrastructure, material science and all sorts of stuff that wasn’t there. I think that there have been generations of really deep thinkers about education, including Illich, including my own professor, Piaget, who really saw dead on. They knew what to do, but there wasn’t the infrastructure to be able to carry it out on a mass scale.

The ideas were there. The technology wasn’t. Now, we’ve got the technology and too often it’s divorced from the ideas. I think we can put these together. My last book, The Children’s Machine, I spelled this out somewhat that, in a sense, the technology gives us today the infrastructure to put into practice ideas like learning by doing, learning by experience, coaching, all the ideas, but I think that for the same reason that da Vinci simply couldn’t invent the helicopter, however smart he was, these people could not put into practice.

Our own American John Dewey almost a hundred years ago said almost everything about education that we can say today, but it couldn’t take effect because we didn’t have the technological infrastructure.

Chris Dede: If I could build on that, I think one vital difference from the ’60s is the parents and citizens see their workplace changing dramatically in a way that wasn’t true then. As a result, there’s a growing consensus that the kinds of skills that are important in today’s workplace are also important in today’s classrooms.

Alan Kay: Just one small sentence. Many of the writers of the Constitution thought that a new Constitution should be written every 20 or 30 years by each generation. This is Jefferson’s view, is also the view of Tom Paine. That’s a little radical, I think. A slightly less radical way of thinking about is, what they really wanted was each generation of Americans to reinvest themselves in their democracy by thinking that they had a strong part of reframing it. That’s even a radical idea today, but I think it’s actually very much in tune with what America has been about.

George Brown: That’s what the Republicans are trying to do today.

Alan Kay: Is that right? I’ll have to study closer.

George Brown: Illich’s book was called Deschooling Society and basically he took the whole system apart, not just the classroom, but the whole system. You have any comments, Doctor?

David Shaw: Yes, one minor one. I think that connections between the classroom and education, in general, and the rest of society is actually quite important to the educational process. One of the things that we actually have some evidence about now is that, students who are involved in real world projects and especially projects in which people in the outside world are depending on them for something tend to be highly motivated. They tend to learn tremendous amounts, sometimes about only the very specific things they’re working about, but they learn higher order thinking skills that are extremely important.

One thing that I think that this means is that we have to have involvement in the educational process not just on the part of educators and education schools, and if I can just use this as an excuse to interject this, I have to disagree very strenuously with what Seymour said about the education schools that there is nothing interesting going on there. It’s just an appalling remark. These are people who have given their lives, some very smart people to studying some of these problems.

My PhD adviser always said, “Whenever you see a body of people, even if you disagree with what they’re doing, who are very smart and who are writing a lot of things, usually, there’s something there, and you should try and understand what it is.” I suspect that part of the problem is that it doesn’t agree with Seymour’s own particular model. The fact is, I think we have to involve them. We also have to involve companies, and that’s a key thing.

While I’ve said that the federal government must do a lot, the fact is that, the companies in our society now are going to have to pick up a big part of the burden. That’s one of the reasons that the president just had a meeting two days ago with the CEOs of a number of the top American companies. George Lucas was there, Michael Eisner, Gerald Levin, Ted Turner, and the president, the vice president, the secretaries of Education and Commerce.

The representation of Ron Brown there was an interesting one because it ties in education to society in two directions. One is to help education. The other direction though is that, this administration is committed to education partly because if we are really going to have students who evolve to be able to hold 21st century jobs, high-wage, high-skilled jobs in the next century, it’s not going to happen if they don’t acquire those skills. I think that there are a lot of reasons for having some very close ties between industry, educators, and the students themselves and their parents.

George Brown: Thank you. It’s a sign of my age, but I tend to think of previous explorations of this topic and I’m reminded that Buckminster Fuller delivered a long lecture translated into a book later called Education Automation, which in my opinion was exactly the wrong way to go about changing education, but it was his effort to show how modern technology would affect education. I’m sure this was 30 years ago that he delivered this lecture at Southern Illinois University.

Robert Walker: Mr. Kay?

Bill Clay: Thank you. Some of your technological proposals are quite revolutionary, but I guess the most radical idea that I’m hearing from each of you today is that there’s still a role for the federal government in education. Let me ask you, Professor Dede. When we talk about the future of education here, are they doing the same thing in Europe and Japan? If so, could you tell us some of their relative weaknesses and strengths?

Chris Dede: I think that all countries across the world are still somewhat mired in the idea that mastery of facts is somehow the fundamental goal of education. If we look across the world at different systems, there is a proportionate emphasis on standardized test as the true metric for determining whether or not students are coming out prepared to succeed in life. Unfortunately, there’s a lot of research that shows that those are a relatively poor indicator of how well people actually do 10 years later as parents, as citizens, as workers.

What we are starting to see in Europe and Japan and countries across the world is a shift from the just-like-me curriculum where professors and teachers try to create students who are really brought up just the way that they were, a just-in-time learning while doing curriculum that relies on more sophisticated measures, similar to those that David Shaw was talking about in terms of authentic experiences with problem solving, and then people from different roles judging how well students are doing in terms of that kind of problem solving.

What we’re beginning to see across the world is moving away from teaching what we know and how we know it to what to do when you don’t know, and how you solve problems when you don’t have all the facts at your disposal immediately. As you know from your own experiences, we live in a world that’s like that now. By the time we understand the situation, it’s already changed before it’s possible to act in full understanding of what’s going on.

I think that there are ideas out of Europe and Japan that are valuable, but we have in many ways a unique culture and a unique economic niche in the world. Our challenge is to evolve a truly American response that relies on the fact that our schools are local rather than driven by a national educational system.

Bill Clay: Thank you. Dr. Shaw, you were talking about 15 years or so from now about the cost of making sure we can reduce the cost of this technology. How cost effective is it now? Is there any idea what this would cost us if we implemented some of these ideas?

David Shaw: The answer to that question is a complicated one. First of all, in terms of cost-effectiveness, there is some data, but much of it is with older styles of pedagogical models, older styles of the use of educational technology. To answer that straightforwardly, we know that if what you want to do is teach a bunch of basic skills in isolation, you can do it faster and less expensively this way. I don’t think that’s actually what we want to do.

In terms of what’s likely to happen in the future, I think the best prediction if we handle things correctly would be that, we’re not going to significantly reduce the overall cost of education directly through the kinds of important things we’re talking about. What we’re going to be able to do is educate much better and give people much better ability, as Professor Dede was saying, to solve the real problems they’ll face later on in life when they don’t know all of the answers.

On the other hand, there are some things that actually technology are going to do pretty much automatically in terms of productivity. If we can get a handle on the organizational within schools, some administrative costs are going to be reduced. There are certain areas where I think that that will have an effect, but I think we have to be prepared for the fact that historically, major changes in paradigm, even when they save a lot of money in the long run, in the short term actually result in a decrease in productivity. We’re going to have to be prepared to spend some money to make that transition.

In the long run, I think that we’re going to see a great deal of cost-effectiveness, especially if you’re interested in the outcomes and not just the total cost. In the short term, I think it’s misleading to have a simple productivity model where we will bring in computers, we’ll automate the process in some way, and everything will become less expensive. In some sense, we have no alternative. If the alternative really is that we train people to be competitive with textile workers in developing countries, then in the long run, that’s not cost-effective either.

If we look at this on an investment basis as opposed to an expenditure basis, even just looking at tax revenues alone, we should be able to get extraordinarily high rates of return from every dollar we spend at the federal level, because it’s the highest level of taxing authority and it deals with the problem of economic externalities. That’s the right level to do it. We would expect to get many dollars back in the long run, not just through savings in education, but through increased productivity through basically positioning ourselves in a way such that our country can be economically competitive and can retain the standard of living that we’ve all become accustomed to.

This isn’t strictly an economic problem. We have to be prepared for the fact that if we don’t educate … Up until now, even though everybody talks about increased foreign trade, the fact is most of what happens happens just here locally in the country. That’s going to change. We are going to have a truly international economy. Trade barriers are going lower and I think that’s a good thing over time, but it also means that if we don’t have the skills to compete for the kinds of jobs that are going to be at the top end rather than the bottom end of the pile that we’re going to have to be comfortable having the same standard of living at least for a large part of our population that is characteristic of many less developed countries.

We don’t have any experience as a democracy living in a society where perhaps 75 or 80% of the people earn what might be the equivalent of 30 or 40 or 50 cents an hour. That has never happened here and it raises some important social and political issues. We really have to look at cost in a very broad context.

When my daughter who will be born in 11 days if all goes well is 20 years old, we have no guarantee that she’ll be in the environment she’s in now. The decisions you’re making here about what our educational system will actually look like are going to make a huge difference in that.

Bill Clay: Thank you.

Robert Walker: Mr. Fawell?

Harris Fawell: The picture that I’m getting from you folks, and there seems to be a difference in so far as Dr. Papert is concerned and the rest of you, if I construe what you’re saying correctly, I think there is testimony that 20% of the problem is technology, but I should say 80% is what to do with that technology and the effective use of it, et cetera. Dr. Papert, is that a correct pronunciation?

Seymour Papert: Papert.

Harris Fawell: Papert, you seem to be saying that in so far as having the technology in the classroom won’t be like that piano that, I think, Dr. Shaw referred to where the kids might learn chopsticks, but perhaps not go too far beyond that. You seem to be saying, “Stand back. Get out of the way. We don’t need standards. We don’t need curriculum. Let the ideas and the technology spontaneously come together and you’re going to have some really creative education taking place.”

I would like to believe that. I have trouble seeing it taking place. We haven’t used much of the technology that has come forth so far in the classroom. It’s been very difficult to do that, even. What we really have to find out, it seems to me, is how do we get that technology, first of all, into the classroom. Is it cost, et cetera? Then what do we do about enabling children, especially in the inner city, like he’s saying, in rural areas, et cetera, in a position, first of all, to be able to begin to handle that technology in order to be able to have the access to all that the informational systems will give to us? Can you clarify my thinking a bit on that?

Seymour Papert: Yes, I can. First of all, I did not mean to say that simply putting the technology that it would result in any spontaneously or automatically producing good changes, certainly not. I don’t think the problem is getting the technology there. It’s certainly not in economic terms. In my written testimony, I did some arithmetic that shows that giving every child in the country a computer would raise the cost of education only by 2 or 3%. I don’t think anybody questions that it would produce more than 2 or 3% in increased benefits so that …

Harris Fawell: I found that to be interesting.

Seymour Papert: It only appears to be expensive to schools because accountants have played tricks on technology, computers are on the same budget as pencils, and so they appear to be enormously expensive. If you consider that many school districts, the one in Cambridge, this is exceptional maybe, but they’re spending $10,000 a year per child, and even in poor districts, they’re spending 6 or $7,000 per year per child. You could buy a computer with a lifetime of five years, would be for $1,000 or $500 if we really pushed the industry to do it. That’s $100,000 a year and it’s negligible. I know Mr. Shaw is getting angry, but …

David Shaw: No. No. I’m not angry, but this one, it’s just not correct. Actually, 75 to 80% of the lifecycle cost of a computer isn’t the hardware. That analysis isn’t right.

Seymour Papert: It’s the what?

David Shaw: It’s maintenance. I agree with your point though.

Seymour Papert: Let me make a point, though.

David Shaw: I just don’t want to give unrealistic numbers.

Seymour Papert: I’m sorry. It’s exactly the problem, is that you’re thinking in terms of injecting the technology into the school system as it is.

David Shaw: I agree with that.

Seymour Papert: We have done experiments actually starting in third-world countries where there wasn’t anybody you could pay to maintain them. The kids can learn to maintain the computers. If we only change what they learn so that they could maintain those computers, that would not be part of the cost. The fact that you quote that and it’s quoted all over the place shows how people are interpreting the new ideas in terms of an old framework and so come to misleading conclusions.

That’s my whole thesis that I’m trying to push here, that you need systemic thinking. You need to understand all these questions such as how the thing gets maintained, what the kids learn, how the school is structured, all these have to be taken together as a whole. I think the kids could possibly even make the computers or assemble them. There are all sorts of ways if we really change …

David Shaw: I don’t think that’s a very good idea, Seymour.

Seymour Papert: But it needs to be explored. If you look in the literature …

David Shaw: No. It actually doesn’t. That’s not a very good idea. Now, I agree with your main point and I think we have to look at systemic changes, but representing to Congress that for $100 a year, we can put computers in the school, it’s not doing a service. I actually think it’s a very good idea, the idea of getting students involved in maintaining the computers and doing systems administration, actually not in the low level manual labor, but in many of those tasks.

I think it’s a good idea not largely for economic reasons, but because there’s considerable evidence that that’s actually a valuable educational experience, but we’re kidding ourselves if we think that the … One of the problems actually in the real world right now is that states are evaluating the purchase of computers as if they were capital expenditures in the same way they do when they buy a building and they issue a bond issue and they project the useful life.

The useful life of a computer, first of all, isn’t five years right now. It’s 18 months in industry. Best projections are it would be two to three years in the schools. We can probably involve the students in some aspects of maintenance, but it will not mean [crosstalk 01:11:29] …

Harris Fawell: An interesting debate.

Seymour Papert: Sorry. I know schools with innovative …

Harris Fawell: [crosstalk 01:11:31] with the Congress.

David Shaw: I apologize.

Seymour Papert: I know schools with …

Harris Fawell: Will the record show that Dr. Papert figuratively was pulling hairs out of his head.

David Shaw: Just something out of my head.

Robert Walker: Perhaps we can continue the debate with the next question here. Mr. Sawyer?

Thomas Sawyer: Thank you. I appreciate it. Mr. Roemer was here first.

Robert Walker: I only do what they put in front of me here. They have him next.

Thomas Sawyer: Thank you, Mr. Chairman. It was a wonderful debate and I don’t really want to change the subject because it was going so well. I am interested in a topic that Mr. Goodling touched on and that our answers touched on, but didn’t really get much beyond. That’s the question of what we mean by who we assign whatever the equivalent role of teacher is. We talked about teacher credentialing and teacher preparation, but it seems to me that if we’re looking at that role, it is a role that is changing in itself.

We were continuing to talk about credentials which issued at the beginning of career are sufficient for a 30-year duration at a time when change is a fundamental characteristic of the age that we’re in. We’re really not talking about applying the same kind of seminal thinking to the development of those skills that we bring to whatever is the equivalent of classroom that we are to the application of the technology in learning itself.

What I really want to ask you about is what we seek to prepare teachers to do, how we make that a more continuous process throughout a career. The whole business of the kind of model that we use, is it a Socratic model? Is it a matter of posing questions and framing problems? What becomes the purpose for which we are preparing people to function in this environment?

Chris Dede: As somebody who works in the teacher preparation institution, let me try to answer that question. Historically, some of what we’ve done with teachers, as we’ve said, you need to know your subject and you need to know something about instruction. Much of what you’re hearing from the panel is that, yes, it’s important to know something about your subject, but the subjects now are blurring across a whole range of things that apply to authentic problems, and that knowing something about instruction is perhaps less important than knowing something about learning and being able to think like a learner and being able to facilitate learning.

In business, often what we see now in effective organizations is a community of knowledge in which employees don’t know everything that they need to when some novel problem comes along, but they work as a team, they reach outside of the organization. The really effective employees, the workers and the managers are good at learning how to learn and organizing people to work in teams. I think that some of that is the new role of the teacher.

What’s different between the workplace and the classroom or the learning setting is that the children are not adults and that, often, the teacher has to be able to think like a child as well, and to recognize developmental stages and to recognize how to phrase something in a way that’s appropriate for the child rather than appropriate for a peer. I would characterize the kind of shift that’s taking place in teaching as partly a spreading out of subject matter to not narrowly specialize, partly understanding how to organize and create a community of knowledge that may reach outside of the classroom, and partly understanding learning in a deep way as it’s appropriate developmentally for the students that you’re working.

Thomas Sawyer: Others?

Alan Kay: I’d like to disagree in a fundamental way, first with your supposition. I went to school 50 years ago. I went to first grade 50 years ago and I think somewhere second grade, I realized that my teachers actually didn’t know very much about mathematics. I was getting interested in it. My father was a scientist. At some point, I realized, “Gee, my teacher actually doesn’t know. I know more than my teacher does right now.” The problem was the teachers didn’t know that they didn’t know.

Will Rogers said, “The problem is not what we think we don’t know, but what we think we do know.” Science has made its way by being very careful about what it doesn’t know and very, very careful about what it thinks it knows. I think that the real change in teachers that should happen is that teachers shouldn’t think that they know their subjects because nobody can and it hasn’t been true for hundreds of years. The biggest problem is that teachers knowing a little bit think they actually know enough to teach it.

Thomas Sawyer: It’s precisely the point behind asking the question in terms of giving a credential at the beginning of a 30-year career.

Alan Kay: What I’m saying is it’s always been true, I think, or at least it was true 50 years ago. The critical thing for teachers is not so much to be trained in their subjects, but to be trained in what they don’t know as to have a good sense; for instance, every scientist that I know of is pretty darn humble about what they think they know in their own field, because they’ve learned enough to realize that their ignorance is abysmal and in fact our ability to characterize the world is not nearly the way it’s portrayed on television.

What you need is an opposite kind of person. You need a person who is constantly saying, “I don’t know, but let’s see how this turns out,” rather than a person that says, “I do know and this is the party line.” I think that is the critical change. Once the person takes that attitude, then they are actually much better at their subject than they ever were before, simple because they’re open to touching more areas of it.

Thomas Sawyer: I think we’ve come to …

Seymour Papert: The same thing. A nice phrase, I think, schools are really not bad places for children to learn because they are bad places for teachers to learn. If we can change the school into a place where what they’re dealing isn’t multiplication tables, but exciting subject matter, the teachers would be learning as well the students in the same process. That’s the only answer. If there’s any credential we would like teachers to have, it’s to be good learners.

I think the trouble is you can take a lot of courses about how to be a good teacher, about instructional theory, and the pedagogy. We don’t even have a word in English for the art of being a good learner, as we have what is to learning as pedagogy or instructional sciences to teachers, to teaching. I think teachers, if they got to be credited for anything, it’s for being good learners so that they can participate in the learning process, model the learning process, set the example. I don’t think they need to know about learning. They need to be good at it.

Bill Goodling: I think the observation goes back to teacher training again, the elementary teacher expected to teach all subjects, very little of any math in high school and no math in college. All of a sudden, they’re out there. At any rate, Mr. Roemer?

Tim Roemer: Do you want to go back to your …

Bill Goodling: No. You’re next.

Tim Roemer: Thank you, Mr. Chairman. We’ll try to get back to that healthy debate that was one of the most entertaining parts of this whole hearing between Dr. Papert and Dr. Shaw.

David Shaw: I hate to say it, but I agree with Papert’s point.

Tim Roemer: You haven’t said anything for a while. We’ll try to get you back into the debate here. Let me say, first of all, in prefacing my remarks that I believe that we don’t need to tinker with the schools either, that we need some basic transformation in our schools. We have many problems there. Technology certainly is not going to be the panacea for all our problems. Let me, as Dr. Papert did, tell two parables. One of them will be a question and then get in the other one.

The first one is bragging about my son a little bit. I have a two-year-old that can get onto the computer, can turn it on, turn on Broderbund software and get into the CDROM of Playschool. He loves it, helps him count and play games and learn so much. It’s incredible technology. To what degree are we putting so much emphasis on even these two-year-olds and 12-year-olds being entertained and having this learning and academic technology? To what degree are we overestimating it?

Let me say that when we said that we thought television would be such a great tool in our schools and Channel 1 and all these things were going to be the latest innovation to help us transform teaching and learning. It has not transpired. Certainly, as Dr. Papert or Dr. Kay might say, we need to transform the infrastructure out there, not just the school and teacher. How can we get this technology, whether it be Broderbund or Edmark, whether it be different computers, whether it be the hardware or the software to go the route to help us achieve this dream that we’re talking about this morning and not go the route that so much commercial television has, where they categorize the Jetson and the Flintstones as educational television?

I think on TV, PBS and maybe Nickelodeon are the only TV stations that are doing much to challenge our children. Dr. Shaw, where do we go to make sure that the private sector and the commercial end of this fulfills this dream that we’re seeing?

David Shaw: I’ve asked exactly that question over the last month or so of at least half of the CEOs of the large educational software companies in our briefings. The answer is different in some respects, but there were a few things that were brought up that were in common. First of all, just understand the basic situation. The reason that the vast majority of the software development effort has gone toward the home market as opposed to the school market has been in part that it’s very difficult, for various reason, very difficult to sell to the school markets, much easier to sell to the home markets.

One problem is fragmentation. Right now, many different states and different regions have different standards for adopting software, some of them very stringent. For the home market, you just produce a product and if you advertise it and it’s a good product and it gets good reviews and so forth, people buy it. It’s much more complicated within the school systems. The exact solution, I’m not sure of, but that is one of the problems that they face.

Another one of the issues that they’re facing now is just the availability of hardware. About 40% of all of the machines in the schools right now are Apple IIe’s, I believe. I know Apple, early Apple machines, for which essentially no software is still being written, because it’s too expensive to write for many platforms. This is not a criticism of Apple, which is doing wonderful things in education. It’s a reflection of some of the economic problems involved in getting modern computer equipments into the school and maintaining them.

Many of the computers that we do have, even contemporary ones in the schools, are not being used, partly because of teachers not understanding them, but partly because they don’t have the resources to keep those maintained. In fact, one of the things the president just announced was something called the Tech Core, focusing on having private sector volunteers provide assistance to the schools to solve some of those problems. It remains to be seen how much of the problem it solves, but at least it’s one issue where I think bipartisan support would be very useful.

Then the other thing is research. In terms of understanding what’s popular and what’s fun to play with at home, there are some fairly easy ways to do that. You use focus groups. You try selling things on a sample basis and you see what sells. In terms of achieving specific educational outcomes, we have to have a better of sense for what the right criteria are. Standardized test scores are fine. If what you want to do is raise standardized test scores, if you want to develop other kinds of thinking skills, you need to be able to specify what those objectives are.

Once we have those, there will be a target for the software companies to shoot for. That will be very helpful. I don’t think there should be one target. We need experimentation. We need thousands of flowers blooming to see what the free market does, to see what teachers want to adopt, to see what works in the classroom. I think there’s a real role for the government in stimulating that without subsidizing it. Software companies don’t want money. They’d like some other things that will help them produce for those markets.

Seymour Papert: I want to say something directly on the question you asked about whether the kind of software that’s accessible to your two-year-old child doesn’t overvalue certain adult skills like learning numbers and so on. I think it …

Tim Roemer: Are you saying, Doctor, that my two-year-old is smarter than I am already. Is that what you’re trying …

Seymour Papert: I think that …

Tim Roemer: [crosstalk 01:25:52]

Seymour Papert: I’ve often said that one of the troubles with our education system is that we’re trying to hurry along children to think like adults, whereas we do much better if we got more adults to think like children, have a kind of creativity and intellectual honesty that we could all try to emulate. That aside, I think there’s an important point here. That is, I think it’s wonderful to see these kids doing that sort of thing.